Over thousands of years, Yellowstone National Park, the first national park in the world, was shaped by one of the most dangerous and powerful volcanoes on Earth.

The first major eruption of the Yellowstone volcano occurred 2.1 million years ago. It covered more than 5,790 square miles with ash. It was one of the largest volcanic eruptions known.

While it’s been about 70,000 years since the last lava flow, the volcano is still active. The ongoing volcanic activity underground is responsible for some of the most stunning landscapes in the area, including half the world’s hydrothermal features like hot springs, mud pots, fumaroles, travertine terraces and—of course —geysers.

Today, volcanic activity isn’t the only factor shaping the park’s environment. A much more powerful force is rapidly altering the landscape.

Over the weekend, the park, which is celebrating its 150th anniversary this year, was hit with historic flooding. The floodwaters changed the course of rivers, tore out bridges, and forced the evacuation of thousands of visitors.

“The landscape literally and figuratively has changed dramatically in the last 36 hours,” said Bill Berg, a commissioner in nearby Park County. “A little bit ironic that this spectacular landscape was created by violent geologic and hydrologic events, and it’s just not very handy when it happens while we’re all here settled on it.”

The Yellowstone River reached highs of almost 14 feet on Monday, far higher than the record of 11.5 feet set more than a century ago, according to the National Weather Service.

Montana Gov. Greg Gianforte declared a statewide disaster and said the Montana National Guard rescued 12 people stranded by high waters in Roscoe and Cooke City.

It was the first time all entrances to Yellowstone National Park were closed to the public since 1988 when a series of wildfires affected over a third of the park.

What caused the historic flooding at Yellowstone National Park?

The Beartooth and Absaroka mountain ranges “received anywhere from 0.8 inches to over 5 inches of rainfall” from June 10 to June 13, the National Weather Service in Billings said Tuesday.

The extreme rainfall combined with snowmelt led to a massive deluge of water that sent two to three months’ worth of summer precipitation down rivers and streams in just three days.

Water levels quickly rose to record depths and led to “flooding rarely or never seen before,” forecasters at the National Weather Service said.

Scientists have long anticipated that the climate crisis would lead to more rainfall and rapid snowmelt in the Yellowstone area due to extreme spring and summer warmth.

A recent report showed average temperatures in the Greater Yellowstone Area rose by 2.3 degrees Fahrenheit since 1950 and could increase another five to 10 degrees in the coming decades.

Every national park in the United States is seeing the impacts of climate change

The impacts of climate change are not unique to Yellowstone National Park.

National parks in the US protect unique ecosystems, biodiversity, and cultural sites in a network of 417 protected areas that cover 4% of the US.

When it comes to climate change, these national parks are on the front lines and are already seeing the devastating effects of a warming planet, from increased temperatures and wildfires to less snowfall and melting glaciers.

According to scientists, the flooding we saw this week in Yellowstone is just a preview of what’s to come at our national parks. Climate change is already causing temperatures to rise across the globe, and a 2018 study shows that national parks are particularly vulnerable to these changes.

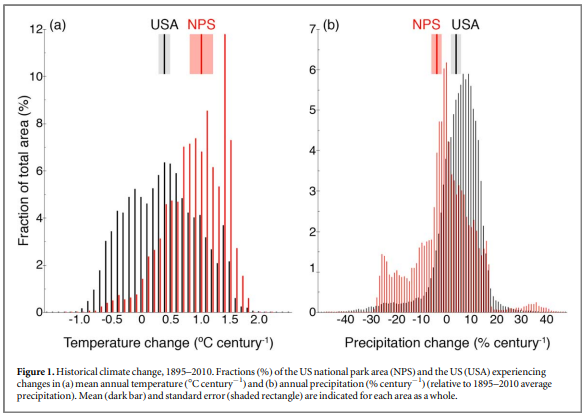

Because so many national parks are at high elevations, in the arid Southwest or the Arctic, they are being disproportionately affected by global warming. Temperatures in national parks are rising at twice the rate of the country as a whole and annual precipitation of the national park area declined significantly to 12% of the national park area, compared to 3% of the US.

One of the most obvious impacts of climate change is melting glaciers. Glacier National Park has lost an estimated one-third of its ice mass since 1966, and scientists project that the park will be entirely glacier-free by 2030.

Higher temperatures due to climate change have coincided with low precipitation in the southwestern US, intensifying droughts in the region. Scientists estimate that the western Joshua tree could lose upwards of 90% of its current habitat in the Mojave Desert by the end of the century dramatically altering the landscape of Joshua Tree National Park.

In August of 2020, a 43,273-acre wildfire burned through the Joshua Tree woodland of Cima Dome. Much of the land is now a graveyard of Joshua tree skeletons. It is estimated that as many as 1.3 million Joshua trees were killed in the fire, as well as countless cactuses, bushes, shrubs, and grasses.

In September 2018, Hurricane Florence caused extensive damage to Cape Lookout National Seashore in Carteret County, North Carolina, with storm surge flooding wiping out visitor facilities, overwashing roads, and causing significant erosion.

The impacts of climate change on our national parks will have devastating impacts on the regional environments

More frequent and intense floods, wildfires, and droughts in our national parks will not only damage park infrastructure and disturb wildlife habitats but also have significant ‘downstream’ impacts on the environment.

Located in the Arapaho National Forest west of Fort Collins, Colorado, La Poudre Pass Lake offers stunning views of the Rocky Mountains. Formed from rain and snowfall, it’s also home to the headwaters of the Colorado River, one of North America’s most iconic and important rivers.

National parks and public lands like the Arapaho National Forest provide ecosystem services, including protection of watersheds that provide drinking water for people and conservation of forests that store carbon, mitigating climate change.

Rising temperatures mean less snowpack in the Rockies, resulting in less runoff to feed our rivers. And that means less water for farmers, ranchers, and communities across the West.

According to a paper published in Nature Reviews Earth and Environment, the Mountain West will be nearly snowless in 35 to 60 years if worldwide greenhouse gas emissions are not rapidly reduced.

The flow of the Colorado River has already dropped 20 percent since the 1900s. Roughly half of that decline is due to climate change, which has fueled a 20-year megadrought across Colorado and the West.

Food for cattle depends on the availability of water in the Colorado River. Farmers and ranchers grow hay to supplement their livestock and rely on grazing permits on public land.

After years of inaction, lawmakers in Washington are finally starting to take action to address the impact of climate change on our National Parks

Conservation of intact ecosystems and protection of endangered species rely considerably on national parks around the world because they form the core of the global protected areas network.

“The West hasn’t been this dry in 1,200 years,” Senator Michael Bennet recently said during a Subcommittee hearing on Conservation, Climate, Forestry, and Natural Resources Hearing on Western Water Crisis. It was the subcommittee’s first hearing since 2013.

Watch: Senator Michael Bennet opening remarks at the Hearing on Western Water Crisis

.@SenatorBennet explained that the Colorado River, which brings water to much of the American West, is running dry. pic.twitter.com/i0bLesKr6H

— RuralOrganizing.org (@RuralOrganizing) June 7, 2022

“If we don’t get our act together in Washington, it’s going to not only put Western agriculture at risk but the American West as we know it,” he said.

“The Colorado River Basin is the lifeblood of the American Southwest. It provides the drinking water for 40 million people across seven states and 30 tribes. It irrigates five million acres of agricultural land. It underpins the West’s $26 billion outdoor recreation and tourism economy,” Bennet said. “And it is running out of water.”

The water crisis is not limited to the Colorado River Basin. The most recent data from the U.S. Drought Monitor found that more than 50 percent of the entire contiguous United States is experiencing severe drought.

The two largest reservoirs in the basin, Lake Powell and Lake Mead, are at the lowest levels since they were filled over 50 years ago. Lake Powell has dropped more than 30 feet in the last few years.

“When hurricanes and other natural disasters strike the East Coast, or the Gulf states, Washington springs into action to protect those communities,” Bennet said. “But we haven’t seen anything like that kind of response to the Western water crisis, even though its consequences are far more wide-reaching and sustained than any one natural disaster.”

Senator Bennet, a member of the Senate Climate Solutions Caucus, has joined with a bipartisan group of legislators led by U.S. Senators Chris Coons (D-Del.) and Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) to streamline the federal response to climate hazards that threaten human health and well-being, critical infrastructure, and natural systems through the introduction of the National Climate Adaptation and Resilience Strategy Act (NCARS).

The bill creates a Chief Resilience Officer role in the White House to coordinate strategies across agencies and create a roadmap to address acute shocks and daily stressors from the growing threat of climate change.

“Addressing these threats requires a whole-of-government approach, and the Chief Resilience Officer in the White House is vital to ensuring coordination and collective action,” Ranjani Prabhakar, Senior Legislative Representative at Earthjustice, said in a statement. “This bill makes it possible to have intentional, proactive conversations across government and within communities for a stronger, more resilient future.”

“I deeply worry that if we don’t act urgently on climate change, it will make the American West unrecognizable to our kids and grandkids,” Bennet said. “I refuse to accept that, and the people in my state refuse to accept it.”